- Home

- Criena Rohan

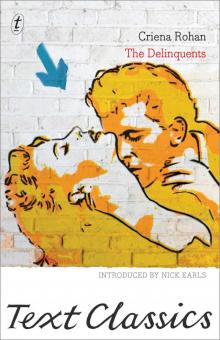

The Delinquents Page 10

The Delinquents Read online

Page 10

‘They’ll be company for you,’ he said.

So they were, for a couple of months, and then Mavis and Lyle set out for Sydney. In other words, they fled from Brisbane leaving their debts behind them. It was fun while it lasted. Lyle was happier than he had been in months. At dead of night he brought the precious radiogram across to Lola’s flat: ‘It’s only a matter of time before we get everything settled up,’ he explained grandly, ‘and then we’ll come back and collect it. If we leave it behind that old bitch over there will take it for back rent.’ Indeed their landlady had been threatening this course of action for some weeks past, and the hire-purchase company had been threatening to claim the bike, and they owed Nick about eight pounds for groceries. As Lyle said, ‘When you gotta go, you gotta go.’ He was very fond of this phrase and repeated it frequently.

He had thought of Mount Isa, where money was good and jobs were plentiful, but every time he mentioned it Mavis said the heat would kill her and Sharon Faylene; and when he spoke of going alone she would collapse on the bed, such a pitiful sobbing blonde heap as would have made anyone give way out of sheer pity and irritation mixed in about equal parts.

‘For God’s sake, Lyle, let’s stay together whatever happens,’ she would beg. So Lyle evolved this romantic plan of running away to Sydney.

Everyone was very gay the night before they left. Final plans were discussed at Lola’s to avoid all risk of eavesdroppers. Even so, they spoke in dramatic whispers, interrupted with much half-hysterical laughing.

‘Now remember,’ Lyle kept saying to Mavis, ‘you’re supposed to be taking Sharon Faylene into the City Hall for her injections and leave those three napkins on the line to put them off the track.’

Next morning he went off on the bike, ostensibly to work. Actually he had been out of work for almost a fortnight—a fact which had tactfully been kept from their landlady. About a quarter of an hour later Lola went down the street. She was wearing high-heeled scuffs, a wide black skirt spread over the stiffest underskirt in Brisbane and she carried a small wicker case. She looked cheerful, innocent and jaunty—in a word, Lola in her usual attire for doing a little morning shopping. She bought some bananas and a packet of rusks, and, strangely enough, a squashy plastic animal of no known species which smelt of caramel; then she waited on tram stop No. 7 till Mavis appeared with Sharon Faylene in her arms.

‘How is she?’ asked Lola with an anxious glance at Sharon Faylene, who looked positively debauched this bright morning.

‘Grizzling all night with her teeth,’ said Mavis, ‘and she’s had three teething powders already since yesterday evening. I do hope they don’t move her bowels on the bike, I’m sure.’

‘Here’s a tram, thank God,’ said Lola.

‘Everything’s going fine so far.’ Mavis sounded almost cheerful again so Lola forbore to say, ‘We haven’t made home base yet.’ But she felt it, and she must have known something, for when they got off the tram just outside the Palace Hotel they were met by Lyle with the sweat standing on his forehead. He said:

‘This corner’s alive with frigging coppers. One’s had his eyes on me for ten minutes; I thought you’d never come. Listen, I’m getting across the bridge. I’ll meet you there.’

Lola looked at the policeman on point duty and at another by the walls of the hotel, who was manhandling a half-caste prostitute who used the beat outside the South Brisbane station. It was obvious that he was working himself up into a very ugly mood, with great gulps of the glorious drug of brutality, and that within a few more seconds he would become dangerous.

‘Let’s get going,’ said Lola. ‘You’d better take me on the pillion, it doesn’t look as strange as loading on Mavis and the kid and they’ll think you’ve been waiting for me.’

They rode across the bridge and a few minutes later Mavis came puffing up, complaining, of course, of the heat. ‘Shall we go up to the City Hall,’ she suggested desperately. ‘We’ve got to go somewhere.’

‘God no, not there,’ said Lyle with justifiable irritation. ‘It’s a hive of coppers too, and all their pimps drink in the “Albert”.’

Where were they to go? That was the question!

Lola had a sensation, not new to her, that perhaps they should not go anywhere. Perhaps they should just evaporate and save the atom bomb the embarrassment. At last they decided to go to Coronation Drive where it was usually fairly quiet, and Lyle went ahead and the women dragged along—Mavis miserable and Lola angry.

‘If you ask me, all Brisbane’s full of coppers and all of them bastards,’ she said, expressing in one concise sentence the full theory of central government of the sunshine State.

‘Well, if I can’t get somewhere to sit down on Coronation Drive I’ll throw myself into the river,’ threatened Mavis.

The teething powders now took effect a little earlier than the time forecast, and Sharon Faylene had to be taken into the ladies room of a pub and washed and changed. Lola did it and found that she wanted to weep.

‘There you are, Sharo girl, right as rain again,’ she said. ‘I’m surprised at you dropping your guts to a few coppers. I’ll carry her a bit,’ she told Mavis. ‘You’ll be holding her in your arms enough.’ So the little procession went on, and at last caught up with Lyle waiting for them under a jacaranda tree.

Mavis sank gratefully down on the seat under the tree, and then the case was opened and there, packed ready to transfer to the haversack strapped to the seat of the bike, were most of Sharon Faylene’s poor little clothes, and a bottle ready mixed, a spare skirt for Mavis, and Lyle’s black shirt and pegged trousers.

Lola packed the haversack in silence.

‘I’ve got some clean napkins in my bag,’ said Mavis, eager to show that she still had a full grip on the situation.

‘And, Lyle! I remembered to leave those nappies on the line.’

Then they all fell silent, and suddenly Lola began thrusting the bananas and the caramel-smelling animal at Mavis and saying:

‘Well, here’s a few things. Try and persevere with her, Mavis, when she has her banana. I know she slobbers all over the place, but she does love it so; and do you really think all those teething powders are good for her? I think you ought to try a Dover tablet crushed up in orange juice. The orange juice will do her good if nothing else, and here’s a fiver to come and go on, and you’d better get going now.’

Mavis leaned across and kissed her.

‘You’re a good friend,’ she said, ‘the only one I ever had in Australia.’

‘Thanks for everything,’ said Lyle, ‘and goodbye for now.’

‘So long.’

Lola watched the bike till it was out of sight, then turned and started walking back towards the city. It was not yet midday. She had all the time in the world. She was alone again. She felt the familiar feeling of loss and emptiness. She wondered if she would get herself a job, or if she would go to a show, or if she would go into the Grand Central and have a drink and see who was there, or if she would have some lunch in town and do some shopping; and she decided against all these things. She went home and locked herself up in the flat. She pulled down all the blinds and locked all the windows. Then she buried the clock under a pile of cushions so that she could not hear it tick; she turned the tap tightly, for she knew by past experience how a dripping tap could thunder through a muffled flat, and she went into her bedroom, stripped off all her clothes and crawled into bed. She pulled the sheet up over her head and straight away the sleep came swirling round her. She felt she was floating. She felt the soft warmth creep around her body and relax all her limbs, and so she slept away the whole afternoon—all the unendurable time. For she could take no more sudden partings—now they affected her like a sickness, a shock. Too often she had been brave and kept herself busy, gone to a show—now there was only sleep, and when she awoke she was reborn. It was about four o’clock that the noise from the street came filtering through into her wombworld, and she opened her eyes and lay on her back staring a

t the ceiling and stretching her arms above her head. Then, suddenly, she remembered that Mrs. Abbott (Mavis and Lyle’s landlady) would very probably be over to enquire about Mavis and Lyle—their whereabouts, and, what was more to the point, the whereabouts of their few possessions—and she shot out of bed, tingling with excitement, ready for anything.

She wrestled and shoved the radiogram into the wardrobe and locked it there.

‘Be quiet and don’t growl if the old lady visits me,’ she told it.

That important business over, she took time off to get into brassiere, briefs and matador suit. Then she brewed herself a cup of tea and turned the wireless on full blast. She danced around the kitchen, doing intricate little jive steps as she prepared the evening meal—poached eggs, baked beans and some spinach.

‘Got to keep up the old strength,’ she told the wireless announcer. She had eaten, cleared away the dishes and was sitting catching up on her mending when Mrs. Abbott arrived.

‘I suppose you know what I’ve come about?’ said that lady.

Lola said, ‘Should I?’ Then she turned down the wireless, and waited with the attitude of politeness and insolence, carefully blended, that she kept especially for landladies and women police.

‘Do you mean to say that Mavis and Lyle never told you they were going?’ said Mrs. Abbott.

Lola shrugged her shoulders.

‘I know nothing about it,’ she said. ‘How do you know they’ve gone?’

‘’Course they’ve gone,’ said Mrs. Abbott. ‘Owing me a lot of rent, too. Did they say anything to you about selling the radiogram they used to have going night and day?’

‘Mrs. Abbott, don’t start talking to me as though you were a plain-clothes cop,’ said Lola, ‘or I’m liable to do the lolly.’

‘I would have been entitled to take it for back rent,’ said Mrs. Abbott.

‘Well spoken for a landlady!’

Lola returned to sewing the sequins around the neck of her black jumper—the interview was over.

A few days later Mrs. Abbott sought to revenge herself by sending the man who came to seize Lyle’s bike across to the Hansen’s flat.

‘They might know something about it,’ she said.

Lola routed him in short order. Indeed, she pursued him right down to the garden gate, shouting the age-old war-cry of the sailor’s wife when dealing with duns.

‘If my husband were home from sea he’d deal with you. Very cheeky when there is just a woman by herself in the house…’

There can be nothing in all this world as terrifying as a poor weak little woman whose man is away at sea.

That night she wrote to Brownie.

‘Sharon’s nappies are still hanging on the line over at Abbotts. I see them every time I go past and they make me feel a bit low—they look so ragged and lonely, though I must admit they are becoming a beautiful colour, much better than poor old Mavis ever got them. The sun is bleaching them snowy. I wish old Abbott would take them down. They remind me of old Sharo, who wasn’t such a bad little kid once you got used to the look of her—and the smell. Anyway, we mustn’t be morbid. I suppose we’ll see them all again some day, and meanwhile I am having victory after victory over the squares. Today a man came from the loan company…’

Here followed a ball to ball description of what Lola had said to the man and what the man had said to Lola.

But final victory was with the squares, for the police caught up with Lyle in Tweed Heads, and he was arrested on the double count of fraudulent debt and taking a motor-bike, the property of Universal Credit Loan Company, inter-State, and attempting to avoid repossession of the said bike. The Magistrate said that, but for the fact that the defendant had never been in trouble before and had a wife who was expecting her second child, he would have taken a much more severe attitude…

The defendant seemed to be on the fringe of the bodgie cult which doubtless had contributed to his foolish behaviour…In paroling the defendant he was giving the defendant a chance…

Lola, reading the Courier Mail, suddenly felt a strong rush of affection for Lyle, standing in the dock, wearing his black shirt and bodgie pants (doubtless now very shiny at the seat and knees), and for poor Mavis (doubtless now very pregnant and floppy), weeping in the court, and for Sharon Faylene, looking as though she had been grown under bags (and doubtless still sucking that trusty dummy).

Shortly after this Lola received a letter one morning which read:

Dear Lola and Brownie,

Doubtless you have read of us in the paper—in the social news—as Lola used to say. It was terrible while Lyle was in remand, but we are doing all right now. We are in that big, old, falling-down place at the end of Eastman Street, No. 20. Come down as soon as you can. I have ever so much to tell and cannot come up in case old Abbott sees me and wants to get some rent out of me. Please come soon. Longing to see you both and have a good laugh over old times. Signed Mavis.

P.S. Would you like to move in with us and take out the fiver we owe you in rent? Just a suggestion. If you would rather the fiver I can let you have it the pay after next.

Lola took the letter into the bedroom to Brownie. He had arrived home two days before and had paid off laden with wages, overtime and accumulated pay. Lola pointed to the postscript.

‘What do you think?’ she asked.

They pretended to discuss it sensibly, but both of them knew that unless No. 20 Eastman Street was a hopeless hovel they would go there. Lola summed it up:

‘All that cheap rent, Brownie. We wouldn’t have to work for ages. We could just be together.’

The two rooms Mavis and Lyle had taken over were terrible. The mark of Mavis’s housekeeping was upon them. Terrible is too mild a word. They were hellish. In one corner stood a bucket of Sharon Faylene’s napkins. They were soaking till Mavis got around to washing them. They looked as though they had been waiting some time, and in the meantime they were a prime attraction for the blowflies that zoomed around in heavy black swarms. In the other corner was a sink where cockroaches had frisked undisturbed for twenty-five years, and they were damned indignant about the intrusion of Mavis and Lyle. Against one wall was a doddering table, and on what had once been a gas stove there stood a two-burner primus. It was glued to the stove by a mixture of splashed fat and boiled-over stew; and when Lola and Brownie entered it was smoking away like a very old tramp steamer. It was heating a bottle for Sharon Faylene. Mavis had the bottle standing in a saucepan in which she was also boiling Lyle’s white socks. Sharon Faylene, clad in the usual napkin, was crawling amongst the matches and cigarette butts that littered the floor. Occasionally she found a dead cockroach and Lola noticed her thoughtfully eating one, but decided it would be beside the point to mention it. And over everything poured the exhausting sunshine of a Brisbane March. It streamed through the window that could not be shut or shuttered. It streamed over the dirt and decrepitude and pointed up every hole in the floor and crack in the walls; and it turned poor exhausted Mavis into a perspiring heap, distressful to see, as she sat on a kerosene box pulling herself together with a cigarette. She shrieked, and then wept with delight when she saw Lola and Brownie.

‘Gawd, it’s good to see you again,’ she kept saying, as she led them in to show them the bedroom. This was slightly better. True there was no bed. All three of them slept on a double-bed mattress and a pile of grey blankets thrown in one corner; and from the way they smelled it was obvious that Sharon Faylene had not yet been trained out of bed-wetting. But at least it was cool and quiet, and the door and window worked; and when Lola looked up she saw that the ceiling was high and beautiful, plastered in a design of scrolls and frond-like leaves, with here and there in the corner a hint of the gilding that the damp and weather had not yet washed away.

‘’Course it’s a bit rough yet,’ said Mavis. ‘But when I get organized we’re going to do wonders. Lyle’s buying a bed this pay. He’s got a fabulous job now in the Cold Storage. Gawd, I should be put into it myself.’ She

wiped her sopping brow and went on:

‘The sink is not too good. Sometimes the water runs and sometimes it doesn’t; and then, when you pull out the plug, there must be something wrong with the pipe because it just runs straight underneath the house, but I don’t suppose it matters because we’re up on such high stilts anyway.’

‘How is the dunny?’ asked Lola, who had never quite become accustomed to the lack of sewerage and the prevalence of gastro-enteritis in Brisbane. ‘Does it have a chain?’

‘It does,’ said Mavis with a touch of the house-proud in her voice. ‘It’s down under the house, and the wooden part of the seat has gone long ago, but there’s plenty of water, plenty of it. In fact there’s so much that the cistern flows over; and if you’re going to be there any length of time you have to go down in your raincoat, and you should see all the ferns that are growing around it—terrific. Lyle calls it El Grotto. “Why bother to go to Capri?” he says.’

Brownie stood fingering a frond of bougainvillaea that had grown through a window and was creeping along the wall.

‘Couple of seasons and this’ll have all this wall down,’ he said.

He took the heavy purple flowers, pushed them back outside and wrenched the shutter closed. The room was filled suddenly with gloom and dusk, and outside on the wooden shutters the bougainvillaea rustled angrily.

‘Listen to it,’ said Lola. ‘It’s furious, Brownie. This was one house it was going to eliminate and you’ve stopped it for a little while.’

Brownie was back in the kitchen looking at the wood stove.

‘Does that work?’ he asked.

‘Don’t know,’ said Mavis. ‘I’ve never tried it. Haven’t been game.’

He rattled the flue and half a hundredweight of soot crashed down from somewhere.

‘It should be all right with a bit of a clean out.’

He looked around, the fierce light of Scandinavian house cleaning in his eye.

The Delinquents

The Delinquents